Monday, March 26, 2012

Oral History: SGT John "Jack" Fenwick, Combat Artist

When did you go to Korea?

I went with the first and second replacement drafts which went from Japan together. We landed right after the Wonsan landing. We then went to a repo [replacement] depot and then were assigned to our units.

Were you involved in “Operation Yo Yo?”

Oh, yes, and then I saw some action at Chosin Reservoir.

What do you remember about that?

I’ll never forget that. We were very lucky. We went all the way up the plateau at Yudam-ni in the Taebaek Mountain Range, which are huge mountains. Unfortunately, they were having the worst winter in memory and it came sweeping down. It was about minus 25 or 30 degrees. Of course, the Chinese were there waiting. We were lucky because when we got to the main supply garrison--Hagaru-ri--there was a fork in the road. It was the only road up there and that was the big problem. It was a primitive, winding one-lane dirt road. Our whole battalion had to pull over to the side to let a regiment of the Army Seventh Infantry Division pass through. They went east of the Reservoir and we went west of the Reservoir. In a few days, they got slaughtered up there. They had no cohesive command. They were all scattered around. It was a butchery.

When we got to Yudam-ni, there was a big hill--Hill 1282--a huge mountain. That was one of the company outposts and we were supposed to relieve Easy Company, 7th Marines but by then it was starting to get dark. This was 27 November. Because of the darkness our battalion stayed at the foot of Hills 1282 and 1240 and we were there when the big Chinese attack came. Easy and Dog Companies, 7th just about got wiped out. We clawed up in the dark to reinforce them.

They started hitting us about 9:30 or a quarter of 10. They were great night fighters; they loved attacking at night. Wave after wave of them hit. It was just unbelievable! We got relieved the next day. We had a lot of casualties because they couldn’t contact the Easy Company command post. So they sent our squad across a long saddle to see if we could link up with them. Three big mortar rounds came in and landed right on our squad. Wham, wham, wham--just like that. I was slightly wounded. The guy in front of me took most of the burst; the guy behind me took most of the other burst. I got one in my back and left leg, which wasn’t too bad. Another guy got it in the upper thigh, which broke his upper thigh bone.

There was a lot of confusion. We were pretty much on our own then so we went down the mountain again to try to find an aid station. When we got to the aid station there were so many wounded piled up it was just impossible. The officers wanted to know what unit we were from. “If you’re still walking we need you back on the lines right away.” So, the walking wounded were right back on the lines as long as you could fire a weapon and walk

So, you got sent back.

Yes, and it scared the hell out of me too. We didn’t see to much more action because we had been set in a blocking position behind somebody. I think we had about 20 percent casualties that night. Other units had 60 and 70 percent and more. A lot of friends of mine got killed up there.

Then we fought our way down to Hagaru-ri, the main garrison. We had it pretty rough there. We were the fighting rear guard going out. We took some casualties from sniper fire and a couple of mortar bursts.

What did Taktong Pass look like?

It was a huge mountain mass rising up on both sides. You could almost look straight down on one side. If you started sliding off the road, you just kept going. These diesel tractors that were towing the big 155 howitzers ran out of diesel fuel and created a roadblock at the rear of the column. With all this confusion, the engineers made a bypass to get around it and blow that bridge, and then Chinese sappers came and blew it out again. So they sent us up on a hill to get a couple of machine guns that were working over the convoy. It was pretty bad. Some of the drivers started panicking trying to get around this roadblock. There were knocked out vehicles all over the place. Any vehicles that came in from Yudam-ni were pathetic. They were all piled with dead Marines on the outside and tiers of wounded Marines on the inside. And they were all shot to pieces.

You said you had been wounded on the first night. What kind of treatment did you receive for your wounds?

Really nothing. They said, “That’s not too bad.” It sounds callous, but if you could see the wounded that were coming in. For each corpsman, there must have been 50 wounded. They couldn’t even perform surgery it was so cold. They couldn’t get IVS in. They started carrying solutions under their parkas to keep them warm. But from the IV to the tube to the man’s arm, it would freeze solid in the tubes. They carried morphine syrettes in their mouths. It was unbelievable.

So they didn’t do anything for your wounds. They simply said, “We’ve got a lot of business here. We don’t need to look at you.”

Yes. It was so damned cold the blood would freeze. I did get frostbite in both hands and my feet. The feet were the worst. Everybody in a line company out there got frostbite.

You had those crazy boots--the shoe pacs. What did those look like?

Something like big galoshes. They were leather and rubber. I guess the theory was good if you were driving a truck or a tank. But if you were infantry. . . The theory was that you had a felt inner sole that was interchangeable. And heavy socks. Your feet would get real warm when you were on the move and make your feet sweat. The bad thing was that when you were immobilized, especially when we lost our packs. . . You were supposed to have two spare sets of felt liners to put in and spare socks. We didn’t have anything. Consequently, within a half hour or so, if you stopped, your feet just froze solid. All your sweat turned to ice.

Do you have any lingering effects of frostbite today?

Oh yes. I’ve got it real bad now. I just got finished with a long bout with the VA.

Do your feet tingle? What kind of symptoms do you have now?

Loss of feeling, loss of toenails, discoloration and swelling, sweating. It’s a little hard to walk sometimes.

Eventually, you got to Hungnam.

We got to Hagaru first. And we said, “We’re all out of it now. This is heaven.

Little did you know.

We went 5 or 6 days and nights with no sleep, no food, no nothing, and constantly on the move. The average Marine up there lost from 18 to 20 pounds in just a few days. We met some Royal Marine Commandos on the way in. They were supposed to go out and destroy those tractors towing the guns we had abandoned. But there were so many Chinese coming in behind us, they couldn’t. They had to knock them out with an air strike the following day.

That night they put us in a warehouse on a concrete floor with 55-gallon drums of wood burning. It was so smoky you could cut it with a bayonet, but it was like heaven to us. We fell asleep, then got hot meals, Tootsie Rolls, and that kind of stuff.

The next morning they got what left of us together and had the corpsmen check our feet for frostbite. Some of them were bad--the toes were black and gangrenous. Those guys had to be evacuated. Then they said, “If anyone thinks they can’t make it, let us know now. You can ride shotgun on the convoy when we break outa here.” That turned out to be the following day.

The engineers had pre dug some positions for us on a small hill that we were to cover. It was on the road coming from Yudam-ni. You couldn’t dig yourself. You’d break your hand on your entrenching tool trying to dig into that frozen ground. The only way they could set the trails of the artillery pieces and baseplates for the mortars was to break the earth with C-4 charges. This hill turned out to be a natural approach. The big hill that was overlooking the bridge--the only way out of town--was held by the Chinese. That was East Hill. Our Second Battalion was there trying to hold on to that.

We had the rear guard again. They hit us really bad about 9:30 or a quarter of 10 that night. They started probing and then coming on wave after wave. We had an airstrip behind us to our left where we were flying wounded out. But we held even though we had pretty heavy casualties. We killed a lot of Chinese that night, about 350 right in front of our platoon. They just kept coming, wave after wave after wave. I had a whole case of hand grenades--that’s 24 grenades plus my own grenades--about 34 in all. I was an automatic rifleman. I had magazines in my automatic rifleman’s belt plus they gave me an extra belt. Before daybreak I was out of ammunition. And I was really sparing my ammo. There was a lot of hand to hand fighting. They would come right in the holes with you. But we held and got out.

Then we went across the bridge. As we started across, I noticed the engineers setting shaped charges to blow the bridge, which went across the Chanjin River. We then had to go back and man the hill again because the convoy was held up. When we rejoined the rear of the convoy I was the last Marine out of Hagaru-ri as they blew up the bridge behind me.

So you managed to get down to Koto-ri.

Yes. We rested up there for a couple of days and then as we moved on down the temperature got warmer, perhaps 10 degrees. We were still getting sniper fire and a few mortar rounds but we stayed primarily on the road.

Some time after Chosin you were wounded very badly. How did that happen?

That happened during the second Chinese offensive. We took a hill unopposed.

Where was this?

At the Hwachon Reservoir in April of ‘51. There was a lot of wild garlic growing there. The Koreans love their garlic. I was a squad leader. My squad was protecting a machine gun on a point. We had a defensive line set up. For some reason, I woke up at night. The guy next to me was supposed to be on watch. I checked him and he was asleep. It was raining. I kept smelling a strong odor of garlic. I said, “Uh oh, the Koreans are coming.” They were climbing the hill and I could smell the garlic coming from their mouths. Then a heavy machine gun opened up from a ridge across from us.

The next thing we knew, we were overrun because everybody was doping off and they captured our machine gun.

Doping off?

It was supposed to have been a 50 percent watch and maybe 1 out of 50 were awake because everyone was so exhausted. So we paid for it and lost a lot of men that night. One of them threw a grenade. I saw it coming. You could see sparks coming out of it. It landed right on the parapet of my fighting hole. I ducked down as it went off. Thank God it was a concussion grenade. I just got splinters in both hands and my right wrist and face. But the flash of the blast temporarily blinded me. It was like a flash bulb going off in your face. My ears were ringing. I tried to stand up to get out of the hole but kept falling down. The guy next to me was wounded and I grabbed him and also tried to drag another guy back by his jacket. We had to keep yelling because by then the perimeter had fallen back and reformed. We had to make sure they didn’t shoot us as we came in.

But we survived that and about a week later we moved up a valley and took a hill that wasn’t supposed to be occupied. When they tell you that, that means look out. Anyway, we took this hill. There was a fire fight and we were pinned down and got real low on ammo. They had a huge Russian 120 mm mortar. They hit at the base of the hill and started walking it up the hill. I said, “Man, we’re going to die here!” I gazed up over this little bank which barely gave us cover and my helmet got shot off. I saw a guy about 5 feet in front of me shot through both elbows and he couldn’t even push himself up. He was looking at me, his eyes big as silver dollars yelling, “Please help me.” I told the other guys to cover me as I yanked him in. There was another guy about 20 feet past him lying on his back. He was a BAR man. I got a grenade in each hand and pulled the pins. I knew we were going to die there so I figured I’d take some of them before I went.

There was a big low bunker to our front with two machine guns in it. I didn’t know it but when I jumped up and went over the bank, there was a North Korean on my left about 30 feet away with a burp gun. He opened up. With luck, I lobbed the one in my right hand and blew him up. He put a couple of bullet holes in my pants legs. I threw the other grenade into the bunker and grabbed the other Marine by the suspenders but noticed that the whole top of his head had been shot off. I dragged him back anyway because we needed his ammo belt and BAR. Then I got two more grenades and finished off that bunker. They wrote me up for a Navy Cross but I didn’t get it until April of ‘61.

So, you were uninjured.

They shot my canteen and helmet off. And I had bullet holes in my pants. It was all fate as far as I’m concerned.

What about the wounds that almost killed you?

This happened on a stupid patrol we went on. Somebody wanted a prisoner to see what the enemy was up to, I guess. By then I was a machine gun squad leader. The captain called us in and told us he wanted a prisoner to interrogate. He told me that I was short and would be relieved in 2 days, and then would probably be going home. He then said I didn’t have to go on this patrol. We had a brand new green lieutenant who had only been with us 2 days. I figured I had better go because he’d need some advice. A good officer will listen to his NCOs or guys who had some combat experience.

Anyway, we went out before dawn. The lieutenant disobeyed orders and got us all fouled up. We ended up in the enemy lines. You could hear them talking and starting their cooking fires. It was scary as hell. We then pulled off that hill and instead of going right back to our lines and taking advantage of the heavy ground mist, the lieutenant said, “Let’s try that other hill.”

Where were you?

Northeast of Inje. We were close enough to the ocean to have naval gunfire of the battleship Missouri supporting us. So the lieutenant said, “Let’s try this other hill,” and we went down a valley. The platoon sergeant who outranked me kept telling him we had to get back to our lines. “You can’t make a name for yourself out here because you’re gonna get everybody killed.”

Well, the mist burned off and we were exposed out there, almost like someone had turned on a light switch. Then one shot rang out. A friend of mine, Lyons from Texas, was at the point and got one right between the eyes. We were only 50 yards from some of their bunkers, maybe even closer than that.

We ran behind a nearby knoll but they continued to fire at us from two sides and the front. We got the machine gun set up on the knoll and began to answer fire. But it was like taking a motorcycle and running up against a tractor trailer. We had literally hundreds of them shooting at us.

So, the whole platoon got shot to pieces. The lieutenant then called in supporting artillery and when they registered in, they landed on us right on the hill. I guess he fouled that up too. Finally, they corrected that, and the shells began landing on enemy lines. By then, just about all of us were hit. Our machine gun was out of ammunition and was by then knocked out.

I grabbed the M1 of the dead kid who was lying beside me. I saw some of the enemy trying to work their way around our right and get behind the hill where all our wounded were. Our corpsman, Glen Snowden was from Texas--a great guy, a World War II vet. I was the last guy alive on that knoll. He was treating the wounded below. I raised myself up to shoot at these infiltrators trying to outflank us and that’s when I got it. I got four hits in the body--machine gun bullets. We were so close I could feel the muzzle blasts.

The machine gun was that close?

Yes. It was a Russian light machine gun. When you were there a while you could tell every weapon firing at you. He nailed me four times. It’s indescribable the way it felt. It was like being run over by a train. I was bent backwards and it turned out that two of the bullets grazed my spine. I could feel everything else except for my legs. It was horrible pain.

Doc Snowden came running up and grabbed me. He checked everybody else real quick and saw that everybody else up there was dead. He said, “I’ve gotcha; I’ll get you out of here.” As he started pulling me, the machine gun got him twice in his left shoulder and knocked him right down the hill. He scrambled right back up again. One arm was hanging down and useless but he still grabbed me and got me out of the line of fire.

He began telling the unwounded riflemen how to dress guys’ wounds. I had an artery severed on my left flank and the exit wound in my back was the size of a fist. Apparently the bullets had hit my ammo belt and tumbled.

So, the bullets entered your body from the front and exited the back.

Right.

And they missed all your major organs?

Well, some hit my small intestine and I eventually lost 18 feet of my small intestine, which is nothing. If they had hit my large intestine, that would have been real bad.

What did Snowden do for you at that point?

Well, he dragged me out of there with one hand. When I finally got back to our lines I told the guys to write him up for a Silver Star, at least. He saved a lot of guys besides me. He grabbed a jacket off one of the dead Marines and rolled it up into a ball. He was all out of battle dressings. He then put it against that hole in my back and took another jacket and tied it around me real tight to stop the flow of blood, you know, like a compress. And that’s what saved me. A Marine company was fighting their way to extract us.

When did this happen?

It was 5 October ‘51. I’ll never forget it.

So, what happened at this point? Snowden was also wounded and there was no one taking care of him. He’s taking care of everybody else.

He had some morphine syrettes left. He told a BAR man, [CPL Richard]Baiocchi

to give me some morphine. He said, “Here, I’ll give you some morphine. He stuck the morphine syrette in my shoulder. I was looking into his face and saying “Thank you, pal,” or something like that, and just as I was looking right into the guy’s face, a machine gun burst hit him right in the jaw and sheared it off. His whole chin was gone. He also took six rounds between his wrist and elbow.

The BAR man was trying to give you the morphine?

Yes. But unfortunately, I didn’t get the morphine because as he got hit the impact snapped the needle off while it was still in my arm. The pain was unbelievable. It was like someone had opened me up with a scalpel without any anesthetic and then filled your insides up with red hot embers. I forgot to mention that when Doc Snowden grabbed me two more bullets got me in my left upper arm. One was a graze and the other went through the flesh real quick.

After Snowden got through with that compress, two Marines grabbed each of my feet and dragged me face-down back through the rice paddies. They were under such fire that they had to run. They dragged me on my face through all that muck. It’s a wonder I didn’t drown. When we got back a ways they put me on a litter. I really thought I had died because when we got halfway back, I felt warm and peaceful. All the pain left me. While I lay face down on the stretcher, I saw a real bright orange hazy light but there was no pain. I remember thinking, “Thank God, it’s all over.”

Right about then there was an air strike on the enemy position and that pulled me out of it. It really made me feel good thinking that the ones who got me were getting fried with napalm.

So, you were still conscious at this time.

Right. We got back to our own lines. On the reverse slope of a hill they had dug out a helicopter landing pad and we also had surgeons on the line by then. They gave me morphine at the base of the hill, then another one when I got up there. They didn’t think I was going to make it. They could only bring one chopper in at a time and get two wounded on them. There were so many wounded, they could only take the ones who had a chance of making it. Of course, some of them went down the hill on stretchers.

A chief corpsman told one of the surgeons to look at me. I remember he had a big walrus moustache. “Sir, you had better look at this man. It looks like his color’s still good.” The doctor then said, “Take one of them out of the basket and put him in.” The other guy was a rifleman from Texas. He had four bullet wounds stitched across his chest. He was in one basket and I was in the other. He didn’t make it. And he had three kids at home.

We went back to Easy Med. That was quite an experience, too. I remember being very scared. They put me on a slanted wooden table and cut all my clothes off. I had a pair of Army tanker boots I had stolen off the Army, a really nice pair. I begged them not to cut them off but they did. Then they put a catheter in my penis. I think the surgeon’s name was [LTJG Howard] Sirak. He and the other surgeon really put me at ease. And then with his finger he drew a line on my stomach and said they were going to make a small incision. That was no small incision. They ended up cracking me open--a laparotomy! He later told me they put 837 sutures in me. Rather than making a colostomy, they kept snipping perforated small intestine off and re-sewing them.

Where were you when you woke up from the surgery?

I was in the med tent and it was dark. It was night time. I only saw one Coleman lantern at one end of the tent. I was laying on the cot and felt all warm and sticky on one side. I had dysentery once and thought I had messed myself. I called a corpsman who came to me with the lantern. He said, “Don’t worry, it’s just blood.” I had blood and plasma going in both feet and both arms--IVS. There was a Levin tube coming out of my nose, another tube in my penis, and another coming from the exit wound in my back.

The next morning both surgeons and Doc Snowden came in. He was all patched up with his arm in a sling. They told me they had to get me up on my feet. I said, “You’ve gotta be kidding me. I’m dyin’ here. I can’t feel my legs; I can’t move. He said, “When we got in there we found three vertebrae that were just grazed by the bullets and were fractured. But you have what they call spinal shock. The feeling will return. We can practically guarantee it.”

But I was really worried I was going to be a paraplegic. But for the grace of God, another eighth of an inch, I would have been.

Did the bullets go completely through you or did they have to remove any fragments?

No. They tumbled their way through me. But I got peritonitis real bad. I remember by the time I got to the hospital ship I was getting 500cc’s of penicillin a day. It could have been fragments of filthy clothing going through with the bullets, or stuff from the rice paddy, and of course perforated intestines. I remember the day I got hit I hadn’t had anything to eat, just a sip of water. The surgeon said that had I had food in my intestines, that probably would have been it. I wouldn’t have survived.

What was the next stage in your recovery?

The surgeon told me that once I passed wind, he could take the tube out, remove the catheter, cut down on the IVS, and fly me to the hospital ship.

How long were you there at Easy Med?

I really don’t know because I don’t know how long I was unconscious.

How did they get you to the hospital ship?

I saw the ship tied up. I think there were four of us in the ambulance. They took us to an Army hospital train. What an experience that was. These Army nurses came down. I don’t know whether they were having a bad day or a bad week, but boy, they were very different from Navy nurses. They acted like wrestlers and treated us very roughly. One said, “Another damn Marine. You don’t belong on here.”

They put each of us on a litter on the hospital train, then had to take us off, put us in another ambulance, then took us to the hospital ship. They put us in slings and hoisted us aboard.

Do you remember what hospital ship?

The Consolation. It looked great. It was snow white--unbelievable! The ward was so clean and beautiful. I think it was even air-conditioned. I didn’t want to get in that bunk. It was so clean and I was so filthy. There was all the crud from the front plus blood caked all over me. I hadn’t been in a bed in over a year. When they got me all cleaned up and in a bunk, gave me all my shots, and changed my dressings, the nurse, a lieutenant commander said, “How would you like to have some ice cream?” I couldn’t believe it. I thought, I’ll really fool her. So I said, “Yeah, I’d love to have to have some.” And she said, “What flavor?” And knowing they wouldn’t have it, I said, “Rocky fudge.” And then she said, “Coming right up, Sarge.” Then I completely lost it. I grabbed her hand and kissed it. Then I broke down crying. “You Navy nurses are really angels of mercy.” It really broke me up.

I was only there a few days and they flew me to Yokosuka Naval Hospital in Japan. Getting there was hell. We flew in a plane with six engines. And it wasn’t a conventional airplane. It had pusher engines. There were hundreds of wounded on it. There was a lot of brass on hand in Tokyo when we landed because this was the first flight of this kind of aircraft.

The ambulance driver we got must have been the son of a Jap soldier killed by Marines or else he just hated us because he hit every pot hole from the airport to the hospital. I started bleeding again.

It was real late at night when we got to the hospital. They put us in a hallway. When I awoke the next day I was in a sparkling clean ward. There was a whole bunch of sailors walking around. There was only one Marine there. Other than this guy and me, everyone else seemed pretty healthy. The reason why was that this was a VD ward!

They put you in a VD ward?

There were all these sailors and seabees. The guy I mentioned earlier who had his jaw shot off. . . Well they put me on a gurney and wheeled me into his ward to see him. He was in a maternity ward, believe it or not. That’s how many wounded were coming in. They put them wherever they could.

What kind of further treatment did you get for your wounds?

The first thing they did was give me some kind of diluted arsenic to get rid of worms I had. I didn’t need any more surgery but one night I started hemorrhaging and they took me back to surgery. However, they didn’t have to open me up again. I’m not sure what they did.

You must have one hell of an interesting medical record.

Oh, God. I had immersion foot, frostbite--everything. When the surgeon saw me the next day, he looked at the soles of my feet and said, “My God, you could walk on hot embers with these things.” They were so calloused from the frostbite.

Did you ever see Snowden again?

No. I never did. I wrote him for awhile and then we just lost touch.

Did he make it back?

Yes he did.

Do you know if he’s still around today?

No. I’ve been trying to find him for years. I even wrote the Navy. I’d still like to find him.

Well, maybe we can find him.

His name is William Snowden.

I’ll see if I can find him for you. He’d be an interesting guy to talk to.

Oh, he would be. He saved a lot of lives that day. And he went on to serve in our unit after that. He was at the Punch Bowl, Hwachon Reservoir. He was with us the day I got the Navy Cross.

We left you there at Yokosuka being treated in the VD ward. What happened then?

I got friendly with one of the nurses. She was going to take me to the movies one night. They put me on a gurney and she was wheeling me out. She stopped to talk to somebody. There was a ramp. At the end of the ramp was a cactus court. The gurney got rolling and I couldn’t do anything. It hit the wall and I ended up in a cactus bed. It took about an hour to pull all the cactus spines out of me.

You fell off the gurney?

Yes. When it hit the wall I flew off right into the cactus. Luckily I wasn’t seriously hurt. The nurse felt pretty bad about it.

How long were you at Yokosuka?

Probably to the end of October [’51]. They then flew me to Tripler in Hawaii. I was there a few days.

Were you still on IVS?

Yes. Even when I got to Bethesda, once a day they’d hook me up to a drip. It used to drive me nuts.

Do you know what it was?

I think it was glucose and dextrose.

Could you eat solid foods?

Yes. But I still had to get follow up surgery there at Bethesda. The worst thing was they couldn’t go any further with the skin grafts. My spinal cord was actually exposed. A corpsman once showed it to me in the mirror. There was a tube coming out of me with a big surgical safety pin. The pin went through a flap of skin they had by the hole and they’d hook it to the drain tube to hold it in place. Every day or so, they’d pull that drain tube out another inch. That was always a thrill.

Once the tube came out they started packing the wound with silver nitrate to heal it. It wasn’t bad when they packed it in. It was sort of a tingly, itchy feeling. But when they took it out the next morning they had to scrape it out with a spatula. That was something! Sometimes I even threw up. And they always did it right before chow.

It made you sick?

Yeah. It was horrible.

This was the huge exit wound. How big was it?

About the size of a big fist.

How long were you in Bethesda?

Off and on, about 19 months. They used to call me the ox. I was a big strapping Marine about 6 foot 2. I’ve lost about 2 inches in height over the years because I got degenerative disc disease.

Your discs disintegrated?

Yes. Years later. I used to be 6' 2". Now I’m 6 foot.

How long before you fully recovered from all this?

I got back to Bethesda before Thanksgiving but got home for Christmas ‘51.

When did you get out of the Marines?

Later on I went before the PE (Physical Evaluation) Board. By the time I got out it was April of ‘54. I was out for awhile but technically still a Marine. Once the PE Board started I went to the Naval Gun Factory and was stationed there a few months and they called me back to the PE Board. I had to wear a chair back brace. Then they surveyed me out. In ‘54 they determined that I was permanently disabled and then I was out.

What were the circumstances regarding the drawings you did? How did that come about?

I always used to draw even in high school. Back in Bethesda, they wanted us to take therapy. I was doing leather work. That place was fantastic. You were really treated well. I asked for some drawing pads and pen and ink and just started putting some of the stuff down on paper. Around ‘55 or ‘56 or so a neighbor of mine who worked for the Sun Paper in Baltimore saw my drawings and they printed them up in the paper.

They are quite remarkable.

They were printed on a full page in the Sunday magazine section.

Any thoughts about how Navy medicine treated your wounds?

I told my wife that if anything happens to me, the hell with these civilian or VA hospitals. Get me over to Bethesda. I have the highest regard in the world for Navy medicine.

*****************

SGT Fenwick incurred six machine gun bullet wounds on 5 October 1951. Two were through and through wounds of the left upper arm with no permanent bone, muscle, or nerve damage. Four were through and through wounds of the left flank, involving the small intestine, left pelvis, left iliac crest and iliac joint, which was destroyed by direct trauma. There was a large exit wound in the lower, left back adherent to the lumbar spine with fractures of L-3, L-4, and L-5. The left artery was severed. Two of the gunshot wounds were “keyhole” rounds, which tumbled, causing large muscle and tissue damage and loss in the lumbar spine region.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Pearl Harbor Day: Lee B. Soucy

What do you remember about that morning of 7 December 1941?

I had just had breakfast and was looking out a porthole in sick bay when someone said, "What the hell are all those planes doing up there on a Sunday? Someone else said, "It must be those crazy Marines. They'd be the only ones out maneuvering on a Sunday." When I looked up in the sky I saw five or six planes starting their descent. Then when the first bombs dropped on the hangers at Ford Island, I thought, "Those guys are missing us by a mile." Inasmuch as practice bombing was a daily occurrence to us, it was not too unusual for planes to drop bombs, but the time and place were quite out of line. We could not imagine bombing practice in port. It occurred to me and to most of the others that someone had really goofed this time and put live bombs on those planes by mistake.

In any event, even after I saw a huge fireball and cloud of black smoke rise from hangers on Ford Island and heard explosions, it did not occur to me that these were enemy planes. It was too incredible! Simply beyond imagination! "What a SNAFU," I moaned.

As I watched the explosions on Ford Island in amazement and disbelief, I felt the ship lurch. We didn't know it then, but we were being bombed and torpedoed by planes approaching from the opposite (port) side.

What time did this happen?

The bugler and bosun's mate were on the fantail ready to raise the colors at 8 o'clock. In a matter of seconds, the bugler sounded "General Quarters." I grabbed my first aid bag and headed for my battle station amidship.

A number of the ship's tremors are vaguely imprinted in my mind, but I remember one jolt quite vividly. As I was running down the passageway toward my battle station, another torpedo or bomb hit and shook the ship severely. I was knocked off balance and through the log room door. I got up a little dazed and immediately darted down the ladder below the armored deck. I forgot my first aid kit.

What did you do?

By then the ship was already listing. There were a few men down below who looked dumbfounded and wondered out loud, "What's going on?" I felt around my shoulder in great alarm. No first aid kit! Being out of uniform is one thing, but being at a battle station without proper equipment is more than embarrassing.

After a minute or two below the armored deck, we heard another bugle call, then the bosun's whistle followed by the boatswain's chant, "Abandon ship... Abandon ship."

We scampered up the ladder. As I raced toward the open side of the deck, an officer stood by a stack of life preservers and tossed the jackets at us as we ran by. When I reached the open deck, the ship was listing precipitously. I thought about the huge amount of ammunition we had on board and that it would surely blow up soon. I wanted to get away from the ship fast, so I discarded my life jacket. I didn't want a Mae West slowing me down.

Did you dive off the ship?

Yes and no. And that’s an interesting story. Another thing had jolted my memory. I remembered how rough the beach on Ford Island was. The day previous, I had been part of a fire and rescue party dispatched to fight a small fire on Ford Island. The fire was out by the time we got there but I remember distinctly the rugged beach, so I tied double knots in my shoes whereas just about everyone else kicked their's off.

So you did dive off the ship?

Not exactly. I was tensely poised for a running dive off the partially exposed hull when the ship lunged again and threw me off balance. I ended up with by bottom sliding across and down the barnacle encrusted bottom of the ship.

When the ship had jolted, I thought we had been hit by another bomb or torpedo, but later it was determined that the mooring lines snapped which caused the 21,000-ton ship to jerk so violently as she keeled over.

Nevertheless, after I bobbed up to the surface of the water and tried to get my bearings, I spotted a motor launch with a coxswain fishing men out of the water with his boat hook. I started to swim toward the launch. After a few strokes, a hail of bullets hit the water a few feet ahead of me in line with the launch. As the strafer banked, I noted the big red insignias on the wing tips. Until then, I really had not known who attacked us. At some point, I had heard someone shout, "Where did those Germans come from?" I quickly decided that a boat full of men would be a more likely strafing target than a loan swimmer, so I changed course and hightailed it for Ford Island.

What happened when you reached the beach?

I was exhausted. As I tried to catch my breath, another pharmacist's mate, Gordon Sumner, from the Utah, stumbled out of the water. I remember how elated I was to see him. There is no doubt in my mind that bewilderment, if not misery, loves company. I remember I felt guilty that I had not made any effort to recover my first aid kit. Sumner had his wrapped around his shoulders.

While we both tried to get our wind back, a jeep came speeding by and came to a screeching halt. One of the two officers in the vehicle had spotted our Red Cross brassards and hailed us aboard. They took us to a two- or three-story concrete BOQ (bachelor officer's quarters) facing Battleship Row to set up an emergency treatment station for several oil-covered casualties strewn across the concrete floor. Most of them were from the capsized or flaming battleships. It did not take long to exhaust the supplies in Sumner's bag.

What could you do with no supplies?

A line officer came by to inquire how we were getting along. We told him we had run out of everything and were in urgent need of bandages and some kind of solvent or alcohol to cleanse wounds. He ordered someone to strip the beds and make rolls of bandages with the sheets. Then he turned to us and said, "Alcohol? Alcohol?" he repeated. "Will whiskey do?"

Before we could mull it over, he took off and in a few minutes he returned and plunked a case of scotch at our feet. Another person who accompanied him had an armful of bottles of a variety of liquors. I am sure denatured alcohol could not have served our purpose better for washing off the sticky oil, as well as providing some antiseptic effect for a variety of wounds and burns.

Was it a bizarre situation?

Yes, it was. Despite the confusion, pain, and suffering, there was some gusty humor amidst the pathos and chaos. At one point, an exhausted swimmer, covered with a gooey film of black oil, saw me walking around with a washcloth in one hand and a bottle of booze in the other. He hollered, "Hey Doc, could I have a shot of that medicine?" I handed him the bottle of whichever liquor I had at the time. He took a hefty swig. He had no sooner swallowed the "medicine" than he spewed it out along with black mucoidal globs of oil. He lay back a minute after he stopped vomiting, then said, "Doc, I lost that medicine. How about another dose?"

It all sounds like a very incongruous way to practice medicine.

Well, it certainly wasn’t normal but then again, the circumstances were anything but routine. My internal as well as external application of booze was not accepted medical practice, but it sure made me popular with the old salts. Actually, it probably was a good medical procedure if it induced vomiting. Retaining contaminated water and oil in one's stomach was not good for one's health.

Were you still under attack while all this was going on?

Oh, sure. And I remember another incident. A low flying enemy pilot was strafing toward our concrete haven while I was on my knees trying to determine what to do for a prostrate casualty. Although the sailor, or marine, was in bad shape, he raised his head feebly when he saw the plane approach and shouted, "Open the doors and let the sonofabitch in."

Events which occurred in seconds take minutes to recount. During the lull, regular medical personnel from the Ford Island Dispensary arrived with proper supplies and equipment and released Sumner and me so we could rejoin other Utah survivors for reassignment.

When the supplies ran out at our first aid station, I suggested to Sumner that he volunteer to go to the Naval Dispensary for some more. When he returned, he mentioned that he had a close call. A bomb landed in the patio while he was at the dispensary. He didn't mention any injury, so I shrugged it off. After all, under the circumstances, what was one bomb more or less. That afternoon, while we were both walking along a lanai [screened porch] at the dispensary, he pointed to a crater in the patio. "That's where the bomb hit I told you about." "Where were you?", I asked. He pointed to a spot not far away. I said, "Come on, if you had been that close, you'd have been killed." To which he replied, "Oh, it didn't go off. I fled the area in a hurry."

What happened when the Japanese aircraft left the scene?

Sometime after dark, a squadron of scout planes from the carrier Enterprise (200 hundred or so miles out at sea), their fuel nearly depleted, came in for a landing on Ford Island. All hell broke loose and the sky lit up from tracer bullets from numerous antiaircraft guns. As the Enterprise planes approached, some understandably trigger-happy gunners opened fire; then all gunners followed suit and shot down all but one of our planes. At least, that's what I was told. Earlier that evening, many of the Utah survivors had been taken to the USS Argonne (AP-4), a transport. Gunners manning .50 caliber machine guns on the partially submerged USS California directly across from the Argonne hit the ship while shooting at the planes. A stray, armor-piercing bullet penetrated Argonne's thin bulkhead, went through a Utah survivors's arm, and spent itself in another sailor's heart. He died instantly.

The name Price has been stored in my memory bank for a long time as this fatality but, at a recent reunion of Utah survivors, another ex-shipmate, Gilbert Meyer, insisted that Price was not the one killed. I didn't argue too long because I recalled meeting two men at the Pearl Harbor Naval Hospital several weeks after the raid who walked around with their own obituaries in their wallets--clippings from hometown newspapers.

SOURCE

Interview with former World War II pharmacist’s mate second class Lee B. Soucy, a medical laboratory technician assigned to the target ship USS Utah (AG-16). Conducted by Jan K. Herman, Historian of the Navy Medical Department, 11 February 1995.

Pearl Harbor Day: Horace Warden

Were you on the Breese that Sunday morning when the Japanese attacked?

Yes sir. On that Sunday morning we were moored to a buoy near Pearl City. I happened to be aboard the previous night because in those days they used to divide Pearl Harbor into three areas. There was supposed to be a doctor assigned to each area all night for medical coverage. It was my night to be aboard in Pearl City. I was due to go off duty at 8:00 on Sunday morning. I had changed into civilian clothes and was waiting on the deck for a whaleboat to take me to my car so I could go to breakfast at home on the far side of Honolulu. The Japanese hit at five minutes to eight and I never got off the ship.

Did you see them coming?

No. The first thing I remember was the sound of firing and then they called general quarters. We were not a large ship so we were not immediately threatened. After the Japanese delivered their bombs on the large ships they had to come up over us. That's when we got one of them with what I think was a 3-inch gun.

Did you see that happen?

No. I didn't see the plane get hit.

When you went to general quarters, your station was in the sick bay below decks?

Yes. But I didn't have time to get there. I remember one of our food handlers was milling around very upset and crying, a real basket case. We went to where we had the firearms stashed away and we got a rifle and gave it to him. Once he started shooting he was alright. The plane we had shot down landed right near us in the water. The pilot was still alive so they got a whaleboat to go rescue him. Apparently he made a move, put his hand under his vest or something, and so they killed him and then didn't have a live pilot to question. The sailor who shot him was told that he was going to get court martialed. But later that all was quashed and there was no court martial.

We then tried to get underway and out of the harbor. Our ship was ready because we had had the duty the night before, but we were tied to three other ships and they didn't have many people aboard on Sunday morning. So we had to wait until enough crewmembers arrived on these ships to get them out of the harbor.

Did you have any casualties to treat at this point?

None. After about an hour or an hour and a half we were out to sea and started to patrol looking for miniature subs and dropped depth charges. We stayed out about a week and then came back. I can't remember whether we ran out of food or fuel. Anyway, we came back in to Pearl Harbor. Then we could see all the damage that had been done. Going out we couldn't see it because of where we were. While we were out we kept wondering why the big ships hadn't come out.

What did you think of all that damage?

It was just terrible. It was one of those things when you think, what's the world coming to? What's going to happen to us now? Everyone was all set to try to get even if we could, but my family was on the other end of Oahu so the first thing I wanted to do was get ashore and let them know that I was okay and find out that they were okay. That was probably the worst week of the war for me.

What did you do once you got back to Pearl?

We stayed there waiting for further orders. There was nothing really to do. I then got permission to go to the Naval Hospital to help out over there.

Did you still have a lot of casualties to deal with from the attack?

Yes. We still had surgery to do. One of the Japanese planes had crashed in the Naval Hospital yard and I have a piece of it.

Did you still go patrolling with the Breese?

Yes. We would go out for a few days patrolling looking for submarines and then come back to Pearl. I remember that on Christmas day in 1941 we were tied up right at Hospital Point. Meanwhile, my family came out to the Naval Hospital to have Christmas dinner with me. That was a wonderful occasion.

Pearl Harbor Day: Nurse Ruth Erickson

Excerpt from a telephone interview with CAPT Ruth A. Erickson, NC, USN, (Ret.), World War II nurse and later tenth Director of the Navy Nurse Corps, 24 March, 30 March, 6 April, 12 April 1994. Interviewed by Jan K. Herman, Historian, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

In late summer of 1939 we learned that spring fleet maneuvers would be in Hawaii, off the coast of Maui. Further, I would be detached to report to the Naval Hospital, Pearl Harbor, T.H. when maneuvers were completed. The orders were effective on 8 May 1940.

Tropical duty was another segment in my life's adventure! On this same date I reported to the hospital command in which CAPT Reynolds Hayden was the commanding officer. Miss Myrtle Kinsey was the chief of nursing services with a staff of eight nurses. I was also pleased to meet up with Miss Winnie Gibson once again, the operating room supervisor.

We nurses had regular ward assignments and went on duty at 8 a.m. Each had a nice room in the nurses' quarters. We were a bit spoiled; along with iced tea, fresh pineapple was always available.

We were off at noon each day while one nurse covered units until relieved at 3 p.m. In turn, the p.m. nurse was relieved at 10 p.m. The night nurse's hours were 10 p.m. to 8 a.m.

One month I'd have a medical ward and the next month rotated to a surgical ward. Again, I didn't have any operating room duties here. The fleet population was relatively young and healthy. We did have quite an outbreak of "cat [catarrhal] fever" with flu-like symptoms. This was the only pressure period we had until the war started.

What was off-duty like?

Cars were few and far between, but two nurses had them. Many aviators were attached to Ford Island. Thus, there was dating. We had the tennis courts, swimming at the beach, and picnics. The large hotel at Waikiki was the Royal Hawaiian, where we enjoyed an occasional beautiful evening and dancing under starlit skies to lovely Hawaiian melodies.

And then it all ended rather quickly.

Yes, it did. A big dry dock in the area was destined to go right through the area where the nurses' quarters stood. We had vacated the nurses' quarters about 1 week prior to the attack. We lived in temporary quarters directly across the street from the hospital, a one-story building in the shape of an E. The permanent nurses' quarters had been stripped and the shell of the building was to be razed in the next few days.

By now, the nursing staff had been increased to 30 and an appropriate number of doctors and corpsmen had been added. The Pacific fleet had moved their base of operations from San Diego to Pearl Harbor. With this massive expansion, there went our tropical hours! The hospital now operated at full capacity.

Were you and your colleagues beginning to feel that war was coming?

No. We didn't know what to think. I had worked the afternoon duty on Saturday, December 6th from 3 p.m. until 10 p.m. with Sunday to be my day off.

Two or three of us were sitting in the dining room Sunday morning having a late breakfast and talking over coffee. Suddenly we heard planes roaring overhead and we said, "The `fly boys' are really busy at Ford Island this morning." The island was directly across the channel from the hospital. We didn't think too much about it since the reserves were often there for weekend training. We no sooner got those words out when we started to hear noises that were foreign to us.

I leaped out of my chair and dashed to the nearest window in the corridor. Right then there was a plane flying directly over the top of our quarters, a one-story structure. The rising sun under the wing of the plane denoted the enemy. Had I known the pilot, one could almost see his features around his goggles. He was obviously saving his ammunition for the ships. Just down the row, all the ships were sitting there--the California, the Arizona, the Oklahoma, and others.

My heart was racing, the telephone was ringing, the chief nurse, Gertrude Arnest, was saying, "Girls, get into your uniforms at once. This is the real thing!"

I was in my room by that time changing into uniform. It was getting dusky, almost like evening. Smoke was rising from burning ships.

I dashed across the street, through a shrapnel shower, got into the lanai and just stood still for a second as were a couple of doctors. I felt like I were frozen to the ground, but it was only a split second. I ran to the orthopedic dressing room but it was locked. A corpsman ran to the OD's desk for the keys. It seemed like an eternity before he returned and the room was opened. We drew water into every container we could find and set up the instrument boiler. Fortunately, we still had electricity and water. Dr. [CDR Clyde W.] Brunson, the chief of medicine was making sick call when the bombing started. When he was finished, he was to play golf...a phrase never to be uttered again.

The first patient came into our dressing room at 8:25 a.m. with a large opening in his abdomen and bleeding profusely. They started an intravenous and transfusion. I can still see the tremor of Dr. Brunson's hand as he picked up the needle. Everyone was terrified. The patient died within the hour.

Then the burned patients streamed in. The USS Nevada had managed some steam and attempted to get out of the channel. They were unable to make it and went aground on Hospital Point right near the hospital. There was heavy oil on the water and the men dived off the ship and swam through these waters to Hospital Point, not too great a distance, but when one is burned... How they ever managed, I'll never know.

The tropical dress at that time was white t-shirts and shorts. The burns began where the pants ended. Bared arms and faces were plentiful.

Personnel retrieved a supply of new flit guns from stock. We filled these with tannic acid to spray burned bodies. Then we gave these gravely injured patients sedatives for their intense pain.

Orthopedic patients were eased out of their beds with no time for linen changes as an unending stream of burn patients continued until mid afternoon. A doctor, who several days before had renal surgery and was still convalescing, got out of his bed and began to assist the other doctors.

Do you recall the Japanese plane that was shot down and crashed into the tennis court?

Yes, the laboratory was next to the tennis court. The plane sheared off a corner of the laboratory and a number of the laboratory animals, rats and guinea pigs, were destroyed. Dr. Shaver [LTJG John S.], the chief pathologist, was very upset.

About 12 noon the galley personnel came around with sandwiches and cold drinks; we ate on the run. About 2 o'clock the chief nurse was making rounds to check on all the units and arrange relief schedules.

I was relieved around 4 p.m. and went over to the nurses' quarters where everything was intact. I freshened up, had something to eat, and went back on duty at 8 p.m. I was scheduled to report to a surgical unit. By now it was dark and we worked with flashlights. The maintenance people and anyone else who could manage a hammer and nails were putting up black drapes or black paper to seal the crevices against any light that might stream to the outside.

About 10 or 11 o'clock, there were planes overhead. I really hadn't felt frightened until this particular time. My knees were knocking together and the patients were calling, "Nurse, nurse!" The other nurse and I went to them, held their hands a few moments, and then went onto others.

The priest was a very busy man. The noise ended very quickly and the word got around that these were our own planes.

What do you remember when daylight came?

I worked until midnight on that ward and then was directed to go down to the basement level in the main hospital building. Here the dependents--the women and children--the families of the doctors and other staff officers were placed for the night. There were ample blankets and pillows. We lay body by body along the walls of the basement. The children were frightened and the adults tense. It was not a very restful night for anyone.

Everyone was relieved to see daylight. At 6 a.m. I returned to the quarters, showered, had breakfast, and reported to a medical ward. There were more burn cases and I spent a week there.

What could you see when you looked over toward Ford Island?

I really couldn't see too much from the hospital because of the heavy smoke. Perhaps at a higher level one could have had a better view.

On the evening of 17 December, the chief nurse told me I was being ordered to temporary duty and I was to go to the quarters, pack a bag, and be ready to leave at noon. When I asked where I was going, she said she had no idea. The commanding officer ordered her to obtain three nurses and they were to be in uniform. In that era we had no outdoor uniforms. Thus it would be the regular white ward uniforms.

And so in our ward uniforms, capes, blue felt hats, and blue sweaters, Lauretta Eno, Catherine Richardson, and I waited for a car and driver to pick us up at the quarters. When he arrived and inquired of our destination, we still had no idea! The OD's desk had our priority orders to go to one of the piers in Honolulu. We were to go aboard the SS President Coolidge and prepare to receive patients. We calculated supplies for a 10-day period.

We three nurses and a number of corpsmen from the hospital were assigned to the SS Coolidge. Eight volunteer nurses from the Queens Hospital in Honolulu were attached to the Army transport at the next pier, USAT Scott, a smaller ship.

The naval hospital brought our supplies the following day, the 18th, and we worked late into the evening. We received our patients from the hospital on the 19th, the Coolidge with 125 patients and the Scott with 55.

Were these the most critically injured patients?

The command decided that patients who would need more than 3 months treatment should be transferred. Some were very bad and probably should not have been moved. There were many passengers already aboard the ship, missionaries and countless others who had been picked up in the Orient. Two Navy doctors on the passenger list from the Philippines were placed on temporary duty and they were pleased to be of help.

Catherine Richardson worked 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. I had the 4 p.m. to midnight, and Lauretta Eno worked midnight to 8 a.m. Everyone was very apprehensive. The ship traveled without exterior lights but there was ample light inside.

You left at night?

Yes, we left in the late afternoon of the 19th. There were 8 or 10 ships in the convoy. It was quite chilly the next day; I later learned that we had gone fairly far north instead of directly across. The rumors were rampant that a submarine was seen out this porthole in some other direction. I never get seasick and enjoy a bit of heavy seas, but this was different! Ventilation was limited by reason of sealed ports and only added to gastric misery. I was squared about very soon.

The night before we got into port, we lost a patient, an older man, perhaps a chief. He had been badly burned. He was losing intravenous fluids faster than they could be replaced. Our destination became San Francisco with 124 patients and one deceased.

We arrived at 8 a.m. on Christmas Day! Two ferries were waiting there for us with cots aboard and ambulances from the naval hospital at Mare Island and nearby civilian hospitals. The Red Cross was a cheerful sight with donuts and coffee.

Our arrival was kept very quiet. Heretofore, all ship's movements were usually published in the daily paper but since the war had started, this had ceased. I don't recall that other ships in the convoy came in with us except for the Scott. We and the Scott were the only ships to enter the port. The convoy probably slipped away.

The patients were very happy to be home and so were we all. The ambulances went on ahead to Mare Island. By the time we had everyone settled on the two ferries, it was close to noon. We arrived at Mare Island at 4:30 p.m. and helped get that patients into the respective wards.

While at Mare Island, a doctor said to me, "For God's sake, Ruth, what's happened out there? We don't know a thing." He had been on the USS Arizona and was detached only a few months prior to the attack. We stayed in the nurses' quarters that night.

The next morning we picked up our orders in the commanding officer's office. They informed us that we were free until 0800 the following morning, which would be the 27th. That night several of us were invited out and we went to dinner in our white uniforms and capes. We really stood out in a group. Being Christmas, San Francisco was quiet and we were not feeling very Christmasy. We made some telephone calls for ourselves and our shipmates.

When did you leave San Francisco?

We left on the morning of the 28th of December to return to Pearl Harbor. We went aboard the Henderson (AP-1), an old time transport. The ship was really bulging with troops. These were the first troops to go out since war was declared. Too, this ship was talking the first mail back to Hawaii since the war began and included the Christmas mail.

We arrived back at Pearl Harbor on January 10th and we three Navy nurses were picked up and returned to the hospital. It was like coming back to family. A bonding had been created by reason of our common experience beginning on December 7th. Fifty-five years later that bond still exists whenever one meets up with another.

Pearl Harbor Day: Nurse Rosella Asbelle

Telephone interview with Rosella Asbelle, Navy nurse at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, and later assigned to Naval Hospital Oakland's Occupational Therapy Department with amputee patients during the Korean War. Conducted by Jan K. Herman, Historian, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 13 June 2002.

Where are you originally from?

I was born in Oklahoma but we came out to California when I was about 7 years old--a little town called Dinuba near Fresno.

Where did you go to nursing school?

I went to St. Mary's Hospital School of Nursing, San Francisco, CA.

And you were a Navy nurse.

I was very definitely a Navy nurse. I was at Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941.

What do you remember about that?

Everything. I saw Japanese planes coming over. They were so low, they were right on top of the building.

Then you knew Ruth Erickson.

We were all together. Ruth is a very knowledgeable person. I have all the addresses of the 29 Navy nurses who were at Pearl. We try to keep in touch with each other. I think there are about eight of us still living.

I remember vividly the planes flying over the buildings right next to the nurse's quarters. The nurse in the room next to me and I were looking out the window and she gasped, "Ahh, Rosella, it's war." I'll never forget that. The planes were just above the buildings. You could see the heads of the pilots.

Ruth Erickson told me that they were so close that if you had known who they were, you could have recognized them.

That's right. One came over the building so low, maybe at the height of a flagpole. You could see their heads. This grinning Japanese guy probably was thinking, "Boy, we've got you where we want you." I'll never forget that guy with the goggles and the smile on his face.

Did you have duty that morning?

It was 8 o'clock in the morning and I don't remember if I had duty that morning. But it didn't take long before the chief nurse called everybody over to the wards and casualties started coming in. And they continued coming in throughout the day. The heads or toilets were right outside the wards and there was a walkway between the ward and the head. The bodies were laid out like stacks of wood on that passageway connecting the ward and the toilet.

Did you work in the surgical area?

I was in the surgical ward and when they needed surgery they went to the operating room. Later on, I was transferred to the burn ward because there were so many people who were burned from the fires.

I read that you sprayed tannic acid on the burns.

That's right.

You must have seen some pretty horrible things that day.

It was really tragic. These kids were so young and so burned. I remember a radio blaring the song, "I Don't Want to Set the World On Fire," when some kid at the end of the ward yelled out, "Lady, you're too late. It's done been set." At that time, the wards had anywhere from 20 to 30 patients per ward. And I was on the burn ward. These kids were all lined up with tannic acid applications all over.

The saddest thing, though, was having night duty. That's when these severely burned kids would die. And you'd know when that was going to happen. Many a time, I'd sit by the bed of a young man, boy, who was burned, as he died talking about his family. It was generally about 4:30 or 5:30 in the morning when most of them went. You'd hold their hands and talk to them about their families.

That must have been terribly sad for you.

Yes. These kids were so young.

I'm sure that even if you don't remember everything that happened subsequently at Oakland, you'll probably never forget that day as long as you live.

I don't think anyone would.

We've previously posted Nurse Arbelle's entire oral history.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Oral History: Nancy Crosby, USS Haven hospital ship nurse

USS Consolation, Inchon Harbor

USS Consolation, Inchon Harbor

Telephone interview with Nancy “Bing” Crosby, Navy nurse aboard USS Haven (AH-12 ) during the Korean War. Conducted by Mr. Jan K. Herman, Historian, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 26 December 2001.

Where are you from originally?

Baltimore, MD.

When did you decide you wanted to be a nurse?

When I was a little girl. My mother’s closest friend was a nurse and I guess she influenced me.

Where did you go to nursing school?

Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore. Then the Navy sent me to the University of Pennsylvania for my baccalaureate, and then to Boston University for my masters. They treated me very well.

When did you join the Navy?

I joined in 1949.

What do you remember about that?

I was a little nervous. My parents never said they were against it at all. We were kind of a Navy family. We grew up with webbed feet. We spent our summers at the Magothy River off of Chesapeake Bay. I was very delighted because both of my brothers were in the Navy. One went to the Naval Academy, and my other brother served in submarines. I was the only one that had to go to war. Would you believe that? Two brothers in the Navy and I was the only one who went to war.

Where was your first assignment?

Bethesda, MD. Then I went to Beaufort, SC, about 2 years later, and then to the Haven.

How did you hear that the war had broken out in Korea?

I don’t remember much about it except that we were at war, Korea was near Japan, and North Korea had invaded South Korea. I heard they needed nurses because they were commissioning a hospital ship and they were looking for volunteers. I was delighted.

So you actually volunteered for service on the Haven?

Oh, yes. All the nurses were volunteers.

USS Consolation and Danish Hospital Ship Jutlandia

Who was your chief nurse?

Nell Harrington. She’s since died. She was a courageous little lady.

What do you remember about reporting to the Haven?

Oh, my, I was impressed. There was a big red cross on the side of it. It had a few rust spots because the men hadn’t finished all the painting. We painted it on the way over to Hawaii and Japan.

Where did you work on the ship?

I worked on the surgical wards because that’s where most of my naval experience had been. I also worked on the A deck for a while with patients with head injuries.

What do you remember about one of your patients, Sergeant Harry Smart?

I don’t remember him specifically because we were so busy then. We were working 18 hours a day. Patients were coming in so fast by helicopter and landing craft.

When did you get to Korea?

We were there in 1952 and ‘53. We went first to Pusan.

Do you remember CAPT Hamblett, the ship’s skipper?

Oh, Balloon Head?

Why do you call him that?

Because he had such a large head. First of all, he got himself a little car that he kept on the deck of the ship so that he would have transportation when he went ashore. He’d go out with the Korean women. He’d want to date us but after we dated him one time, we swore we’d never go again because he was kind of a lecherous fellow. He was bad news.

But he came up with this idea for the two pontoon floats.

Yes, he did.

Hospital Corpsmen carry a critically wounded patient aboard USS Haven

What do you remember about that?

I have pictures I took of those floats. They lashed them to the sides of the ship with great big cables. Then they practiced landing to ensure that the helicopters could land without too much wind influence on the side of the ship. It worked quite well.

Did you see the first flights land?

I don’t remember whether they were the first ones or not but we watched several of them come in. Then they brought the men up on stretchers, lifting them by litter hoist. It was marvelous.

Smaller copters lashed two stretchers, one on each side. Larger copters held several patients.

Bell HTL-4 aboard one of the Haven's pontoon landing floats, July 1952

Bell HTL-4 aboard one of the Haven's pontoon landing floats, July 1952

And they could land more than one helicopter at a time?

Oh, sure. They could land them on each side of the ship where barges were lashed.

How many on each side?

One at a time on each side.

Were the pontoons decked with wood?

It was wood. They had painted large circles where the copters should land.

How long did you stay on the ship?

I was there pretty close to 20 months.

Were the floats then used while you were in Inchon?

Yes. Later, our helicopter landing pad was built on the afterdeck of the ship and barges were not needed.

I guess that was because you had to stay pretty far offshore because of the tides.

Oh, yes. They were 19- to 21-foot tides; they were impressive. The mud flats used to come out for miles.

You say you took pictures of the floats being used?

Oh, yes. I was impressed by their effectiveness.

How many do you have?

I have about six or eight slides showing the helicopters landing. I also have another one with Nell Harrington climbing into one. I also have slides of critically ill Marines being landed on our helicopter deck on the aft deck of the ship.

How did you get a picture of Ted Williams?

He was a patient on our ship. He was a Marine pilot during the Korean War and was on my ward. When he was getting better I asked him if he would mind if I took a couple of pictures. He was the most gracious fellow.

Marine pilot and Boston Red Sox star, Ted Williams, patient aboard USS Haven, March 1953. Glove courtesy of Haven's Welfare and Recreation Committee.

So he just went up on deck with a baseball glove and posed for you? Where did he get the glove?

Apparently, he kept it with him all the time. He was a neat guy.

Outside orphanage in South Korea.

Outside orphanage in South Korea.

Did any of the nurses ever get ashore to help Korean refugees?

We didn’t deal with Korean refugees until the battles quieted down. Some of the nurses volunteered to work at the orphanages. I never did that. But we used to get clothes from home for the children and we’d take the children on picnics and distribute the clothes. I have some pictures of that. Between battles we cared for Korean children. They were quickly evacuated when we again became busy. In appreciation, the children were brought to the ship to entertain us with Korean dances.

Do you know any of those nurses who may have worked in the orphanages?

I don’t know whether Pat Leisure did that or not. She worked in the operating room.

Did you treat any Korean patients?

Yes. Frequently, our Korean patients had worms. Because farmers periodically used human excreta for fertilizer, many of our Korean patients had worms. They really caused problems. Patients who had abdominal surgery sometimes needed a Levin tube. These were used to suction stomach contents. Worms frequently clogged the tubes and actually came up around the tube and were pulled from the nose.

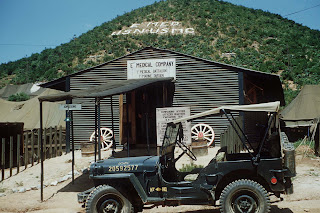

"E" Medical Company, 6 miles from the front

"E" Medical Company, 6 miles from the front

LTJG Crosby aboard USS Haven.

Could you tell me the story of how you and Harry Smart found each other?

It was a delight because he went to a reunion up in North Carolina where he bumped into Frances Omori, the woman who wrote the book about the nurses in the Korean War. She told him that she had interviewed me and that she had my address. So she wrote me and asked if I would mind if she gave him my address. I wrote back to her and said I’d be pleased to talk with him. So he wrote the nicest letter and asked if he could someday come to see me. But we didn’t meet until about 2 years later. Just recently, he drove all the way down to Florida. He lives in Texas, but he was in North Carolina at the time. He drove all the way down just to see me. And we spent 5 hours here talking.

What was that meeting like for you?

Oh, it was very emotional at first. We hugged and cried. It was very warm and touching. I still get emotional when I talk about it. I don’t know where the feelings welled up from but they really were something. I was very, very moved. He made all those years in Korea worthwhile.

He was a Marine patient?

Yes. He says I saved his leg but I don’t remember. But, apparently, I did care for him on the ship. There were so many to care for.

He remembered you because he recalls they called you Bing. And that was your nickname.

Right. Crosby so they called me Bing.

Do you keep in touch?

We write letters and email. He’s a delight. I can’t believe he went to all that trouble to find me.

You were very important to him.

Apparently, I made a difference.

Do you ever think about that time back in Korea?

Yes, particularly when this war’s going on and when they talk about Vietnam. It makes me mad. You always hear about these wars but never hear about the Korean War until recently. And I believe that more of our men were lost in the Korean War than in the Vietnam War.

Surgery Tent, "E" Medical Company, 1st Medical Battalion, 1st Marine Division, August 1952.

Surgery Tent, "E" Medical Company, 1st Medical Battalion, 1st Marine Division, August 1952.

Papa-san smokes his pipe. Pusan, April 1952.

Papa-san smokes his pipe. Pusan, April 1952.

LTJG Virginia Brown, NC, USN, posing beside USS Haven then moored at Pusan, South Korea, March 1953.

LTJG Virginia Brown, NC, USN, posing beside USS Haven then moored at Pusan, South Korea, March 1953.

Friday, October 7, 2011

Oral History: Anna Corcoran, nurse aboard USS Haven during the evacuation of defeated French survivors of Dienbienphu

Telephone interview with Anna Corcoran, nurse aboard USS Haven during the evacuation of defeated French survivors of Dienbienphu from Saigon in September 1954. Conducted by Jan K. Herman, Historian of the Navy Medical Department, 26 May 2004.

Aren't you from Massachusetts?

Yes. I grew up in Boston.

Where did you go to nursing school?

At the Carney Hospital School of Nursing, which at that time was in South Boston. I graduated in February of 1948.

When did you decide to join the Navy?

I wanted to join when I first got out, but at that time, being at the end of the war, they said you needed several years experience. Of course, Korea hadn't yet started.

As soon as we finished, a couple of us went to work in New York and then to New Orleans because we thought it would be fun. We ran into some other nurses who wanted to go to California so we went there. Korea started in June of '50 and I went to Los Angeles and applied to join. In those days, of course, we didn't have computers and they had to send all the material back to Boston to make sure I was who I said I was. So it took a few weeks, and I didn't go in until February of '51 and didn't go on active duty until May of '51.

Where did they send you for your first assignment?

San Diego.

I'll bet you enjoyed that.

I did. I had a great time. All my duty stations were great.

I know that for a nurse to be assigned to a hospital ship was the ultimate assignment at that time. Did you feel that way about it?

Well, I did. But you see, I went overseas to Guam and Japan. Then we were due to rotate home--Ruby [Brooks], myself, and two other nurses. There were about six of us. The chief nurse called us in and said, "You will be having your orders back to the States but would you like to be assigned to the hospital ship?" At that time they had reassigned a lot of their nurses either to Yokosuka or somewhere in the Pacific. So they were short of nurses and asked us if we'd go aboard to supplement their number.

So four of us said yes. When we got back to the States we would come into Long Beach and would then be given orders to our new assignments. We went aboard in Yokosuka in the first part of September '54.

What was your first impression of the ship when you went first went aboard?

I loved it. I had been in Yokosuka and had seen ships going in and out all the time. I was assigned to a three-bed room with Martha Bruce and a Medical Service Corps pharmacy officer--Kay Keating. Kay was the first woman non-nurse to be assigned to a ship.

When did you learn what the ship's mission was going to be?

They told us when they asked us if we wanted to go. They told us that we would be evacuating people who had just been released from prison and would be taking the Foreign Legion back to Oran, Algeria, and the French soldiers into Marseille. So we knew that right away.

What do you remember about your arrival in Saigon?

Saigon was a beautiful city. It was so pretty and the buildings were so white. There were nice roads and streets. We didn't see a lot of destruction or anything like you'd see later. There was a cocktail party for us the first night after we arrived.

Had you and your other nurse colleagues been aware of what had been going on? Had you heard about Dienbienphu and all of that?

Yes, we did. One of our doctors at Yokosuka had been sent up to evacuate a lot of the Christians from the north down to the south part of Vietnam. His name was Dr. Tom Dooley. He was my ward medical officer. He loved life and he was great to the patients. He would push the piano up there and play on the wards in the afternoon. All the nurses were very fond of him, even though some of the doctors were a little envious. Consequently, the Medical Department has never spoken well of him. The CO and XO weren't crazy about him.

He had gone earlier up to Haiphong to help care for and evacuate the refugees. That was called "Operation Passage to Freedom."

That's right.

So you knew about what had happened to the French and that you were going on this mission of mercy to Saigon to pick them up. Did you have any idea before you saw them what condition they were in?

No. I only knew about the Foreign Legion from the movies.

What do you remember about the loading of the patients aboard the Haven?

We loaded them in the middle of the night. And there were two rumors as to why we were doing that. One was that they didn't want the Viet Minh to know how many we were taking, and the other was that it was cooler in the middle of the night. We loaded over 700 patients starting somewhere about 3 or 4 o'clock in the morning. We had them all aboard by 10 o'clock.

Were you up close to this action or were you below decks?

We saw them being loaded. A lot of them walked aboard and some came aboard on stretchers or in wheelchairs.

What was your impression of their condition?